Good and even great films can be hamstrung by going for a PG-13 rating, rather than letting go of the brake and running full steam towards the R-rating that Voyagers so clearly deserves.

Keeping your hand on the brake can either be a clever, artistic way of controlling your art, of showing self-control and discipline, or it can strangle your work and go against the narrative, which promises so much but doesn’t quite hit the mark. There’s a grizzly, sexy, gritty journey of self-discovery trapped inside a made-for-young-adult audience in Voyagers that is disappointing. It’s forty or so years in the future; the Earth is dying, so a crew is bred, created, and sent to a far-off planet so the human race can continue.

A very muted and almost bland Colin Farrell leads the expedition for the eighty-six-year journey, where participants will be created en route. Spliced together from the finest specimens grown in a lab, their sole purpose in life is to procreate through the first two generations, with the third eventually landing on a new planet to create Earth all over again. The film’s setup takes barely twenty minutes to get going; it moves so fast that there is a lot of confusion about what is happening to the planet; is it a virus, global warming, a war? Everything is rushed to get to the point of the film; Lord of the Flies in space.

The cast is solid and have a lot of maturity and control in their performances. Ty Sheridan’s Chris and Fionn Whitehead’s Zac are set up too obviously, and way too early as opposite sides of the good/evil coin. Simultaneously, Lily-Rose Depp is unceremoniously relegated to being the object of the two boys’ desires. A rather childish love triangle tries to artificially ignite drama into the situation where a subtle hand would have developed a more layered approach to the situation. The spacecraft’s contemporary design work and the endless corridors and cramped conditions created by cinematographer Enrique Chediak build a desolation and hollowness that brings back memories of Solaris (1972).

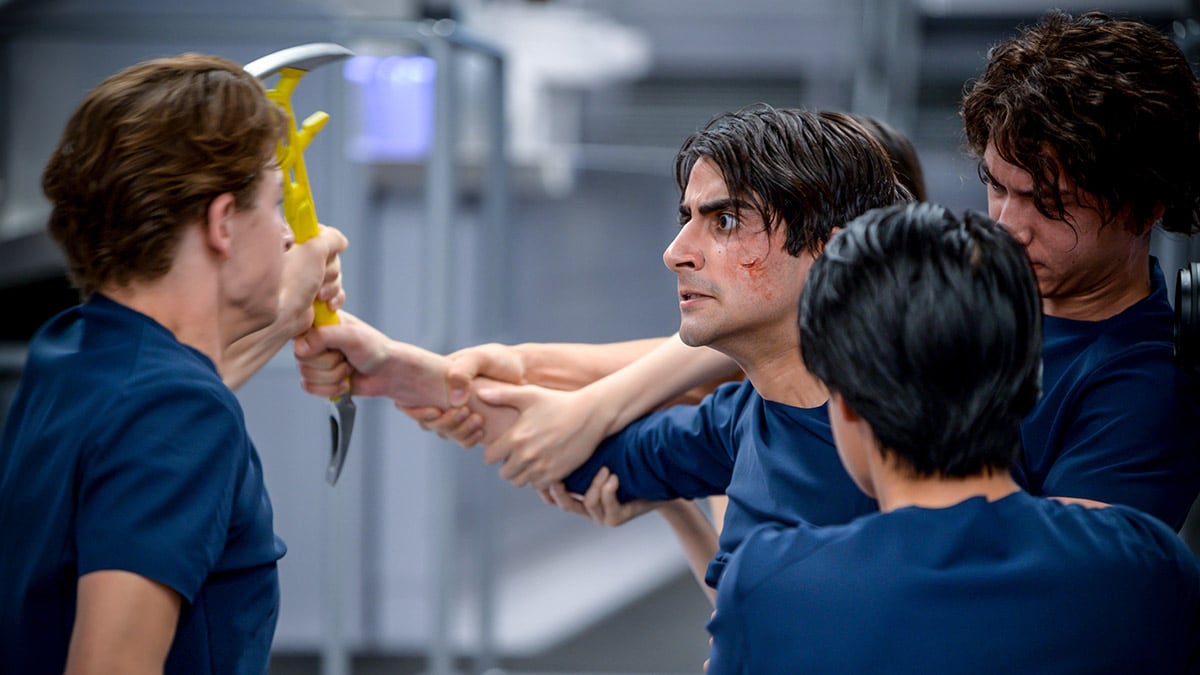

Writer-director Neil Burger’s vision is alluring and stylish but dramatically underdone. For a sci-fi thriller film about the end of the world and a new frontier, with hormonal teens thrust into their first forays into sexuality, individuality and identity, so much of this film is just dull. The premise is not original; everyone from Tom Baker-era Doctor Who to modern video game narratives have used the ‘seed in space’ trope. Some much more effective than others and a lot more effectively than Voyagers. Ironically, the film is relatively self-restrained, given that the whole plot revolves around a bunch of young people liberated from a drug that makes them docile. It suddenly awakens all of their rage, lust, jealousy, euphoria and paranoia in an airtight, sealed environment like lab rats, thus putting human nature under a rather unforgiving microscope.

The questions and possibilities teased by Burger are intriguing; how would submissive, isolated youths grow up without any human influence or experience of life outside the spacecraft deal with the sudden emergence of sexual desire and rampant emotions? Their lives have been a collective of practical skills for maintaining the ship; on day-to-day needs, but how could they possibly understand the nature of sexuality? Consent? Responsibility? Burger is too restrained, too straight to take us anywhere near believability. The heightened emotions felt by the crew of the ship never really connect with the audience. The dystopian post-apocalyptic fall of the master race is hinted at but never fully realised. The brief moments of giddy intensity and crippling jealousy and paranoia are treated on screen like a deodorant commercial rather than anything the audience can relate with.

Richard (Colin Farrell), the lead-scientist who insists on travelling with the crew when they take off as very young children, is their only contact with other humans. He acts like a father figure to them, helping them understand a lot of their struggles within the first ten years of the journey. Here is where is the first colossal plot hole develops and goes supernova into a black hole. It is not a woke or a #metoo issue; it is a logical issue—why would they allow a single man to travel off the planet with a crew full of children, whose sole mission is to be the progenitors of the future generations of humanity? There’s something seriously wrong with that logic. There is no protest, no ethical issues raised, no committee room meeting where Farrell can flex his dramatic muscles.

Ten years race, ahead and we’re suddenly stuck in the middle of a 1990’s Calvin Klein commercial, all skinny leg black trousers and black tees. Once Farrell is out of the picture (no spoilers) and chaos ensues, characters start to think for themselves and question things. However, they’re banging the audience over the head with these questions so much so that subtlety entirely disappears. And, in a rather insulting stylistic choice, found footage of blood and flesh, animals attacking, and volcanoes erupting blaze across the screen—these images are not in the minds of the characters; they’re for the benefit of the audience. After the second time this occurs, suspension of disbelief has all but departed.

The film’s biggest pity is that the script never really grapples with any of the numerous dark implications of the whole plot of creating designer babies in space and sending them off to colonise an entirely new planet. How would their lives, devoid of regulations and laws, except for a computer comms uplink with Earth that will eventually be unanswerable, actually work? How would society even be created by a collective with seemingly no interest in art or culture or myth-making? How do docile, almost-automatons go about creating a society? Voyagers has so much potential to be a dark and harrowing tale, a twisted psycho-sexual cautionary; humanity’s true nature on display, but that concept is so lost on an idea rendered impotent by design.

Another vital question not raised in Voyagers; how does not even one of those kids exploring their identities and sexuality develop any interest in members of the same sex? With roughly twenty, maybe thirty members of the crew suddenly awakening to their hormones and bodies, there is no single gay or bi character? Perhaps, the film is trying to tell us that hetero-normative sexuality is natural and LGBTIQ+ is a choice?

Voyagers is trying to be old school science-fiction that pulls no punches while asking serious questions about science, technology, and the nature of humanity, yet in the same breath, runs away from its premise.

Fun Fact:

Voyagers almost got an R-rating from the MPAA.

COMMENTS