The Exhibition on Screen program delivers a stunning portrait of Van Gogh’s mysterious sunflower paintings in the documentary film, Sunflowers.

There is something truly timeless about great works of art. There’s something that draws you in, crawls under your skin and stays with you forever—like a religious experience. The stillness, colour, and narrative of the painting have always been a symbiotic relationship between art and the viewer.

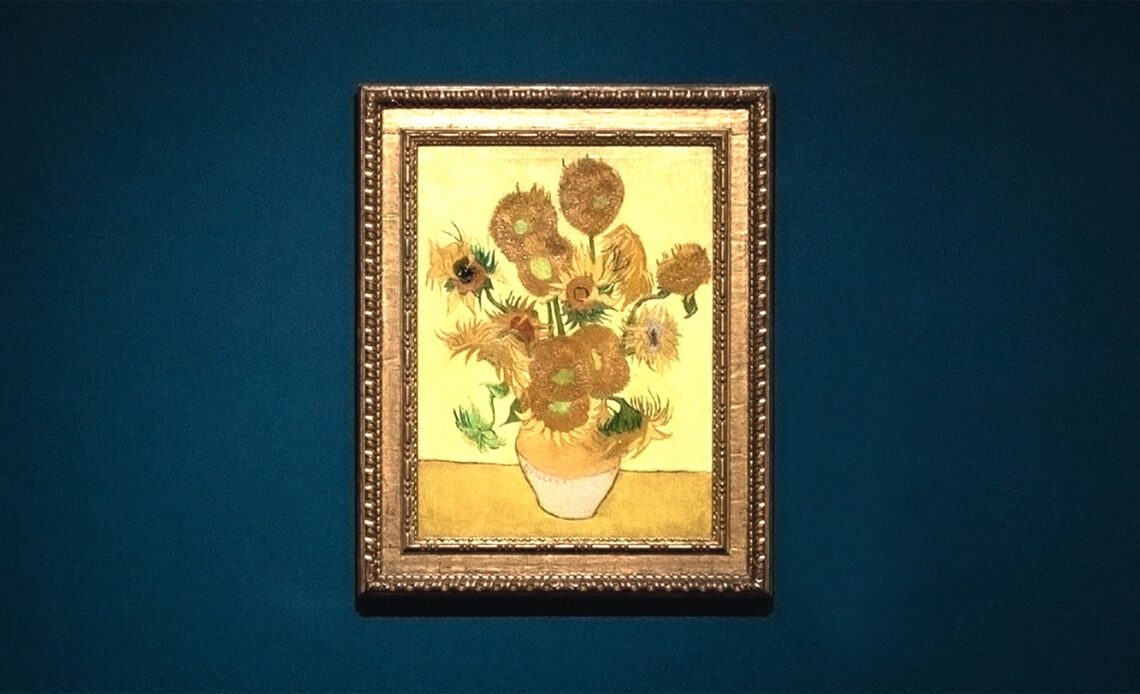

No more is this apparent than with Vincent van Gogh’s famous Sunflower paintings. In an exclusive and remarkable exhibition, the Van Gogh Museum has allowed the team behind Exhibition on Screen a rare opportunity to show the world the five publicly owned versions of Sunflowers in a vase. Of course, we’ve all seen these instantly recognisable paintings before in movies, books, documentaries—even in Doctor Who. This documentary film goes far beyond the surface of the art and explores the complicated history of one of the world’s most complex artists.

There are so many questions and mysteries surrounding these art pieces. The investigation and analysis are thoroughly entertaining if you are an art or history buff, and still, the film digs deeper, trying in earnest to explore the man behind these incredible works of art. Some of the questions this film explores are very interesting regarding the history of the Sunflower—for example, when did the flower itself arrive in Europe, and how had previous artists reacted to it? What was Van Gogh trying to say with his work, and how does that differ from version to version? And what secrets did scientists discover when they analysed the art in detail?

The film explores each of the five paintings and dissects their texture, narrative, and unique histories; who bought them, where they were sold, how they survived Allied and Axis bombings during the second world war. They’ve gone from Amsterdam to Tokyo to Philadelphia, London and Munich. It’s all shot in incredible high-definition detail; the colours and the shapes of the paintings almost jump right off the screen. Sunflowers really is a unique watch, as all five pieces are now considered so fragile that there will never be an exhibition with all five paintings together again.

The documentary also explores the story of the sunflower in European culture, not just in horticulture and art but also in scientific research and medicine; sunflower oil has been used for centuries as a tonic for certain ailments and skin disorders. The flower is also a cosmic symbol; thousands of tiny flowers inside a larger corona have been used in countless cultures for centuries to represent life, the womb, and the galaxy.

The camera work in this film milks its grandeur and the opulence of great galleries with long panning shots of the famous hallways. There’s sterility in the long shots, a cold, clinical atmosphere that often suffocates the artwork on display. Sure, the film is designed for widescreen and high definition, but Van Gogh was not a cold, clinical and sterile artist. He was vibrant and explosive and subtle in his work.

To many people, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers represent more than an exciting period in the late impressionist’s life; they also represent a visual interpretation of hope against despair, a rebellion against depression and mental illness. That is why we’re drawn to characters like Van Gogh; we fall into the trap of romanticising Van Gogh’s mental illness and his tragically short life.

This is where the film starts to lose its credibility. The story of Van Gogh cutting off his own ear and then giving it to a prostitute is a widely known historical legend, one that the Van Gogh Museum perpetuates in this film as well. According to the legend, Van Gogh and the French painter Paul Gaugin were living together as part of an artist commune that Van Gogh was trying to establish and that, after an argument with Gauguin on the evening of December 23, 1888, took a razor and cut off part of his left ear. He then wrapped the piece in some newspaper and gave it to a prostitute named Rachel.

Following this episode, the artist was hospitalised and eventually decided to enter into an asylum for long-term treatment. In the wake of the incident, Gauguin left the Yellow House in Arles, where the two had been living, never to return, although he and Vincent remained in contact. What we do know for sure is that Van Gogh’s ear was mutilated. There are enough documentary sources, and the artist’s paintings of himself with a bandaged ear attest to this fact.

Two German scholars have recently questioned the integrity of the legend. Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans, in their book Van Goghs Ohr: Paul Gauguin und der Pakt des Schweigens (“Van Gogh’s Ear, Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence,” Berlin: Osburg, 2008), argue that it was Gauguin who cut off Van Gogh’s ear, doing so with a fencing sword during an argument over Rachel and their different attitudes towards painting. The book’s claims are based on various sources associated with that night, including police records, Van Gogh’s own letters, and conflicting theories on the artist’s mental condition at the time.

Today, many art historians debate both sides of the argument: Was Van Gogh’s injury an act of self-mutilation in a fit of despair or from a fierce fight with a friend and rival? It is one of those things that we will probably never have the answer to.

While Sunflowers is a visual feast for art lovers and clearly designed for experts and, to some extent, enthusiastic amateurs, its delivery is more like a feature-length commercial rather than anything more probing or insightful. While the re-enactment of Van Gogh’s life is touching and the narration of his actual letters to his brother are revealing, this film still lacks the necessary depth required to really engage with the viewer. The scientific and academic analysis of the works is where this film’s real charm and engagement comes from.

COMMENTS