As the opening credits for Steven Spielberg’s The Post appeared on screen, my nostrils expanded and contracted, picking up a heavy, familiar scent; stale cigarette smoke.

Apparently, one of my fellow cinema-goers had snuck in a cheeky fag, indoors, before the show. As the story quickly catapulted into a distant time; America in the early 1970’s, an age of ornately decorated news rooms filled with smoking men in suits (a time when smoking inside was still normal, and legal), the stale aroma added another layer to the realism, and my immersion, into the busy, journalistic atmosphere. But by the end of the film I had come to be skeptical – was this really the novel Smell-O-Vision I had imagined, or just a bad odour?

On the whole, The Post is a nostalgic fragrance, a perfume of conspiracies from another era, dressed up as a modern day parable on the importance of the press.

Spielberg has rebottled the well known story of the discovery and publishing of the top secret Pentagon Papers, which were discovered by whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, played in the film by Mathew Rhys, and leaked to Neil Sheenan of The New York Times in 1971. The documents detailed secrets regarding the United States’ political and military involvement in the Vietnam War, proof of a wide-scale covert deception of the public, encompassing up to four Presidencies.

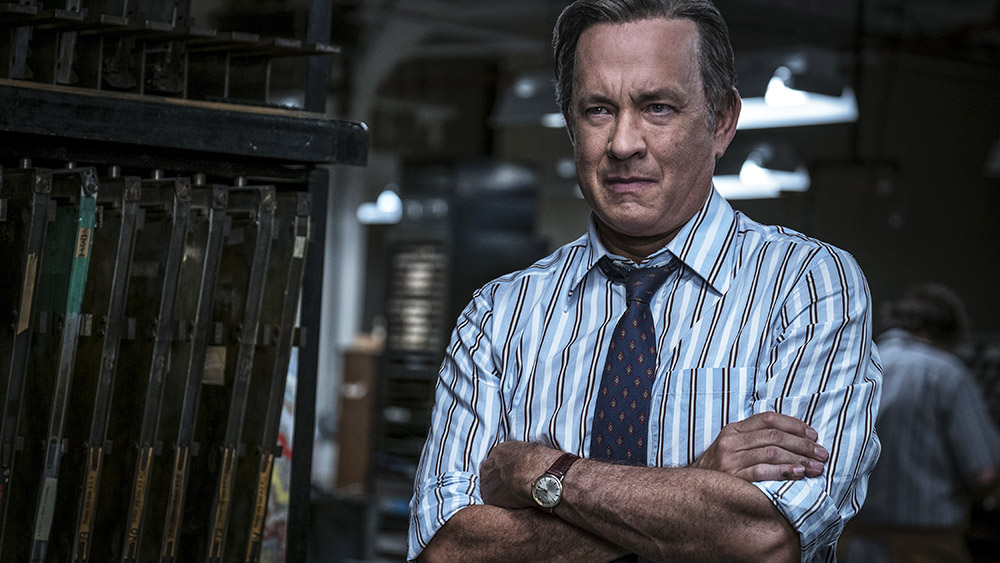

These events, which are so pivotal to US history and its national mythology, have been recreated multiple times in stories surrounding the Watergate controversy (my mind leaps to James Spader’s performance in 2003’s The Pentagon Papers). But Spielberg’s film chooses to focus on events after the historic initial release, and on later releases made by the Washington Post (an interesting choice, as the Post’s chapter of the legend typically centres on journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who would later expose the Watergate conspiracy). Rather, Spielberg focuses on editor Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks as he negotiates with Meryl Streep, who plays The Post publisher Katherine Graham, as they decide whether to release the remainder of the report, which the New York Times had not yet published due to legal pressures from the Nixon administration.

Writers Liz Hannah, Josh Singer and director Spielberg’s intentions are obvious here; to draw comparisons between the struggle of the freedom of the press against government censorship to the modern age of Donald Trump, and his war on ‘fake news’. In fact, the film timely premieres just as Trump attempts to ban the scathing biography ‘The Fire and the Fury’ by journalist Michael Wolff. There is another concept in the film, however, which is more interesting to me personally than a jab at Trump – the difficult choice made by an individual to maintain their moral integrity, presenting the facts, in compromising times.

Daniel Ellsberg is not the central subject of this movie, but he unavoidably remains the pivotal catalyst which triggers all proceeding events. Indeed, the opening chapter of the film trudges through mud puddles, deep into the jungles of Vietnam, following Ellsberg as he first feels the compassion and burst of conscience which would inspire him to defect from his job at the Pentagon and steal the top secret documents. In real life, Ellsberg was motivated after hearing a draft resister named Randy Kehler, who was excited ‘to join his friends in prison’ by making the moral choice to protest against the war. In modern times, Ellsberg has remained a strong and vocal supporter for whistleblowers, voicing support for Wikileaks, Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden.

Oliver Stone’s Snowden (2016), I would argue, shares a greater political parallel with the actual Pentagon Papers leaks, than does this analogy for President Trump’s insane narcissistic war on the press. The revelation of the NSA’s illegal surveillance program, PRISM, proved such a profound level of deception from high levels of the US government, that it is much more comparable to the mistrust and betrayal the information in these papers represented at the time.

But Spielberg is far less interested in the aged conspiracy at the core of the drama, than he is on the triumphant story of the newspaper’s editors, journalists and, of course, feminist icon Katherine Graham, the unlikely female sole proprietor of The Post – and to be fair, Meryl Streep shines as the tough, but warm newspaper publisher, who though overworked, flustered, sleeping in a bed strewn with papers and books, consistently out of breath and clumsy – nonetheless displays the courage and tenacity to push on with the integrity required to make the morally correct decision to publish, which is at the core of the film’s message.

One can’t help but be reminded, by the narrow focus of the film, that Spielberg still embodies and represents the worldview of the ageing, yet undying, ever dominant baby boomer generation. The mythological narrative of the Pentagon Papers coming amidst events as iconic of the era, such as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the free love movement and ‘happenings’ of Woodstock and the ‘Flower Power’ protests outside the Pentagon, has weaved itself throughout popular culture for decades. In spite of the baby boomer generation growing up and abandoning the more youthful aspects of their ideology, the liberal ‘Age of Aquarius’ has come to garner more negative associations in modern times, including potentially creating the environment in which the Charles Manson murders could flourish. But the people-power act of finally bringing a halt to the Vietnam war remains a badge of achievement for that generation, which Spielberg seems determined not to let the public forget.

In an age of rampant right wing conspiracies spread online; from holocaust denial, through to the absurdity of Pizza-Gate, alleged Youtube paedophile rings and lizard aliens running the world, one can be forgiven for wanting to repress the urge to dredge up conspiracies of earlier eras. However it seems important when looking at a film like The Post, to remember that the Pentagon Papers came out at a time when conspiracy theory was a staple of the left, and not right wingers like Alex Jones.

Rampant myths of a link between E. Howard Hunt (one of Nixon’s ‘plumbers’ who were attempting to find information to discredit Daniel Ellsberg when they were exposed in Watergate) existed for many years; Hunt in some theories being identified as one of the three tramps photographed in Dallas on the day of the assassination of J.F.K. It was a wild age for left wing conspiracy theories, which still have resonances today. Recently declassified files on the assassination of Kennedy are pensively being examined, by those still adamant that Kennedy was the target of a coup by his own government involving the CIA, over the bungled Bay of Pigs invasion and Kennedy’s stance on Vietnam. This deep state paranoia lasted for decades after Watergate, explored endlessly by Generation X through books and films, and personified most completely by Chris Carter’s The X Files series, which has been reprised for an 11th season this year; famous for merging conspiracies about a global world power, secret CIA knowledge of assassinations, U.F.O’s, alien colonisation plots, cloning experiments and just about every other aspect of American urban legend.

Whilst these ideas seem absurd and corny in the 21st century, it is worth remembering that one thing the Pentagon Papers did reveal, which is touched on in The Post, was that the US government did play a key role in the 1963 Vietnamese coup and assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem. Proof of CIA involvement in similar assassinations all over the world have since come to light, and those agencies, and individuals involved still have never faced any lasting commissions or trials for the murders. This all may seem highly tangential, with the overarching paranoia surrounding the events of The Post somewhat lost on modern audiences. It’s interesting how little has changed since the setting of The Post, yet how different the conclusions made by the baby boomer generation are today.

Like today, the period of The Post is set in a time when a major US-led war has run for multiple terms (in our case Afghanistan and the war on terror in lieu of Vietnam). An age where whistleblowers constantly bring to light deception and misdemeanours by government bodies like the NSA and the U.S. Military’s use of torture i.e. Abu Ghraib, and criminal behaviour of the head of state (Trump as a surrogate Nixon). Yet the pursuit of justice have all but been abandoned by a tired baby boomer generation who no longer believe in the struggle, but rather primarily in their own righteous actions of the past.

The world, and indeed the media is very different from the 1970’s – in some sense this era has more in common with the days of William Randolph Hearst and the sensational ‘yellow journalism’ of the early 1900’s – which were the ‘clickbait’ and fake news of that period. Nowadays however, the media barons have become multimedia barons, like Mark Zuckerberg. The difference being, in the age of social media we are all journalists, to the point where the responsibility for spreading false information or supporting whistleblowing efforts rests entirely on our shoulders.

Perhaps this is why, for me personally, the character of Ben Bagdikian is the most interesting character in The Post. Bagdikian is played masterfully by Bob Odenkirk, the driven old-school reporter who will go to the ends of the earth to uncover the Ellsberg scoop and dig toward the truth. This theme of personal accountability in getting to the truth seems to me the more potent, if unintentional theme of The Post, rather than a too-easy dig at the absurd Trump administration.

All that aside, the characters in The Post are well played and the film has many subtle qualities worthy of praise. Tom Hanks deserves credit for his version of Ben Bradlee as Hanks utilises a kind of method acting unseen previously in his career. Small traits I noticed whilst watching, such as deliberately puffing his chin out, creates a character who barely resembles the sensitive Hanks, and is overall very convincing as a robust and imposing editor from a different, more patriarchal era.

The film simply looks and feels great. It is a shining example of confident filmmaking of the old school, simple but strong, pulling on every conservative filmmaking technique in the book. Rich sets, and tightly composed mis-en-scene. The style of cinema is so different from the radical, arthouse period of the seventies in which it is set, but this serves as the films merit. Janusz Kaminsky, who has been Spielberg’s cinematographer since Schindler’s List (1993) demonstrates his prowess, as part of the strong tradition and finely tuned craftsmanship of this impressive filmmaker’s team.

The Post is, perhaps intentionally, not ground-breaking, which is in stark contrast to the fervoured exposition of the content of the Pentagon Papers themselves. In some sense, this is Spielberg attempting to cash in on modern political hype, late in the game. Like Ron Howard’s Frost/Nixon (2008), this film is similarly nostalgic to the era of his own coming of age, and whilst the film is masterfully made, beautifully acted, relevant and poignant, there remains a lurking odour of an aged and complacently smug generation who are more interested in pointing out their own achievements, than highlight the true hypocrisies of the day.

Fun Fact:

The strange, and less captivating working title of the film whilst shooting was “Nor’Easter”.

COMMENTS