The first film approved by the Bowie estate, Moonage Daydream, is the third documentary feature by Brett Morgen and by far, his most experimental.

With allegedly five million items available from David Bowie’s archive, the film deploys a bottomless reservoir of the singer’s work to slapdash a full-throttle and immersive musical experience. Moonage Daydream flows like a video essay, similar to Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982), absent of material information but gushing with an ethereal atmosphere. Compiled of never-before-seen footage, interviews and recordings of Bowie, his voice and songs guide the viewer through his worldview.

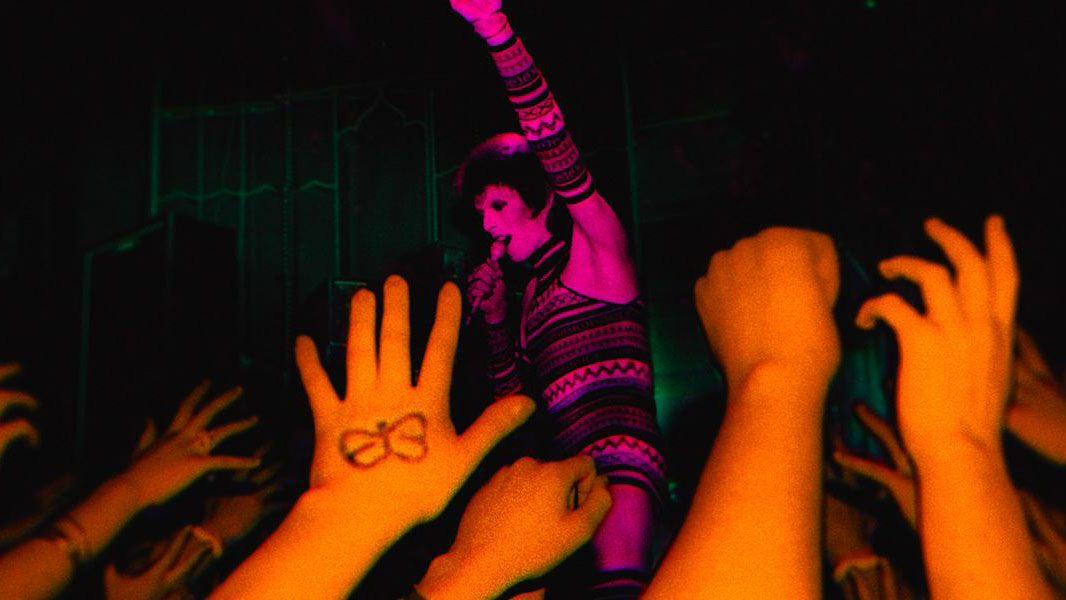

The film announces itself with Bowie’s song ‘Hallo Spaceboy’ reverberating through the cinema. This unrelenting pace sets the tone to match Bowie’s prolific work in many mediums. One news reporter remarks, “it seems as if Bowie has learnt to run before he learnt to walk”. Initially, concert footage is hyper-actively cut with German Expressionism, avant-garde films, and shlock horror to mark Bowie’s ever-expanding interests. Further, his blaring music plays over archival footage of adoring fans crying hysterically to see him, alongside news anchors and interviewees speculating about his so-called origins. Perhaps intentionally, it risks deifying Bowie by blending social commentary of his chameleonic androgyny to elevate him as an other-worldly creature.

The documentary indicates Bowie himself heightened the myth with footage of the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), where he plays the titular alien, as well as rarely seen footage of him in the widely acclaimed stage-play of The Elephant Man. These characters he played trend toward outsiders and estranged figures searching for meaning in a chaotic world. For most of its runtime, Morgen centres on Bowie’s gender-bending Ziggy Stardust period to highlight a global period of Thatcherite and Reaganite unease that Bowie emerged into. An oft-tread notion that Bowie burst onto the scene with unflinching confidence in his inner-self that inspired a generation to embrace their inner selves.

Once the dust settles, a black screen bookmarks milestones of Bowie’s life, with the film effectively narrated by Bowie himself. Recordings of his voice are spliced together to represent his philosophy, as he self-describes as a ‘collector’, ‘generalist’, and a ‘Buddhist by Tuesday and reading Nietzsche by Friday’. In this way, his philosophy adopts a world-weariness as Bowie emphasises that life is transient; it never ends, only changes. Morgen fills these vagaries by threading story through his music, whereby cultural moments inform Bowie’s work and vice versa.

There are also glimpses of mortal insecurities, with Bowie claiming ‘he is a good writer’ but not sure ‘if he is a good painter’, turning down several offers to show his paintings in galleries. Numerous pieces of eclectic artwork are shown amid montages, but each has the central focus of ‘outsiders’. Bowie notes that many depict loneliness, particularly surrounding Cold War era isolation. These duelling components of Bowie hint these varying personas were never Bowie changing his identity but instead evolving it with age and wisdom.

With a meteoric velocity, Moonage Daydream makes the maximum use of cinematic loudspeakers to pump Bowie’s music with restored archival footage of concerts that gives audiences the closest thing to a live performance that is posthumously possible.

Fun Fact:

Texas born and raised blues guitarist, Stevie Ray Vaughan, played guitar on David Bowie’s 1983 “Let’s Dance” album Launching this now legendary guitarist before a world-wide audience. This was the first major album for the Stevie, who in 1990, tragically passed away at the age of 35 in a helicopter crash in Alpine Valley Wisconsin after a two-night show with headliner Eric Clapton.

COMMENTS