Bertrand Bonello’s new film The Beast is incredible. Abundant in scope and brave in its ambition, this is the kind of movie that, for all the right reasons, begs the question, “How did this get made?”.

The Beast is not an intentional crowd pleaser. It’s a slow burn, genre-bending, auteur fantasy that is divisive in length, thematic exploration, and composition. Glued together by Léa Seydoux’s all-time performance, it is both subdued, expressive, commanding, and heartbreaking. I could go on. The film is odd, confident, and feels presented entirely without the presence of studio notes or regard for audience comfort. And I love it.

Centred on Bonello’s unsettling vision of the near future, AI presides over society, eradicating all sense of danger, unpredictability, and error. The existence of human emotion is a threat to the objective operations of a computer-run society. Where most sci-fi films tend to add until it obscures our connection to the world, Bonello takes away. The film presents a grey, dull, boring future devoid of any sense of art or humanity. It’s a little more Brave New World than The Jetsons.

Purposely set in a near future, this bleak reflection becomes more pertinent as a future close enough to touch instead of an unimaginable reality reserved for generations hundreds of years down the line.

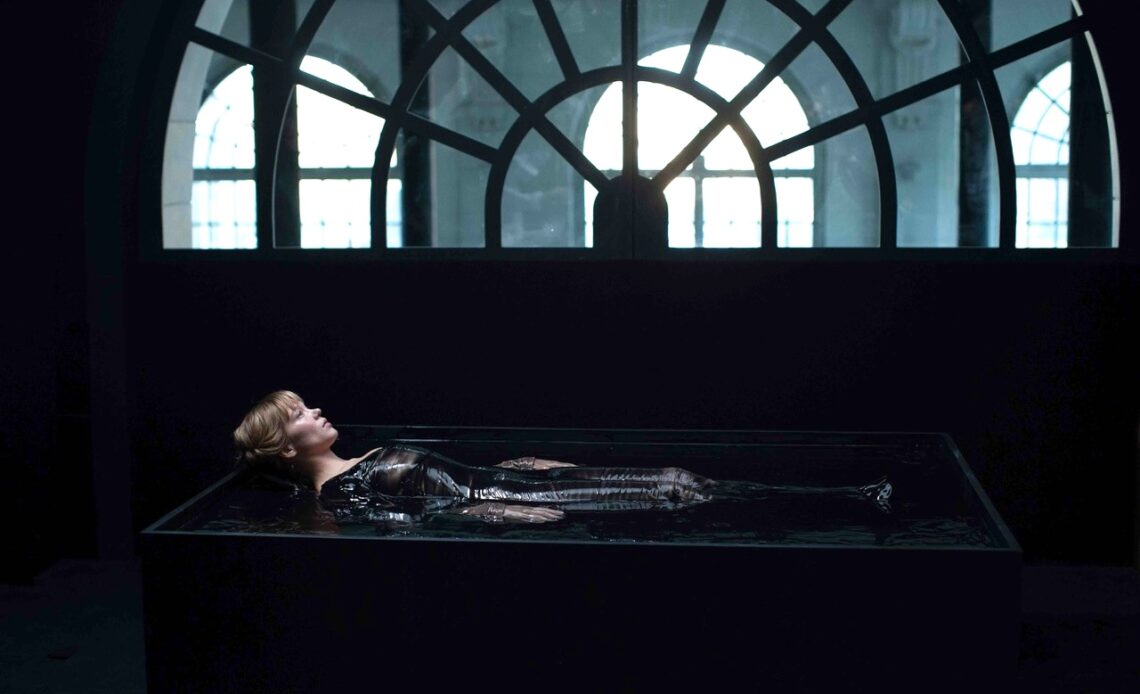

In this vision of the year 2044, Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) is considering a new procedure to “purify” her DNA in an effort to cleanse herself of strong emotions. This procedure should increase her chances of securing employment. Through a process of revisiting Gabrielle’s past lives, it is assumed to resolve all inherited trauma and rectify an unexplained anxiety Gabrielle holds towards an unknown, oncoming cataclysm.

Through this time and genre-bending device, we observe the visions of lives gone by, as Gabrielle meets Louis, played by George MacKay. In each world, be it 20th-century Paris or 21st-century LA, the pair form a powerful yet doomed relationship always destined to end in disaster.

In their present timeline of 2044, the two meet and share a trepidation about the purification procedure. The initial surface-level question posed by the film: “Is it worth losing the things that make us human in exchange for economic benefit?”

Inspired by Henry James’s story “The Beast in the Jungle,” the 1903 novella about John Marcher and his friend, May Bartram. Marcher has an unwavering anxiety that a catastrophe is on its way and, in turn, his life is lived at arm’s length to love and feelings for May, as he awaits an inevitable fate. In Bonello’s take, John becomes Gabrielle, and May becomes Louis. Traversing through time, the ill-fated, tragic love story between Gabrielle and Louis, tinged with existential dread, surfaces throughout the purification process, playing out in 1910 and 2014.

Opening in the Parisian art world of 1910, the first of three time-bending sequences proves to be the strongest. Arguably the portion of The Beast with the most passion, it’s clear that Bonello has a strong affection for the past. Shot on 35mm and casting a nostalgic glow over the sequence compared to the clean-cut digital visions of the future, a married Gabrielle finds herself falling for Louis. Omitting details for spoilers, after a rather long sequence that draws the two together, Gabrielle expresses her cataclysmic anxiety and fear of falling in love. Paris then experiences a true-to-life 100-year flood, leading to an excellent set piece in a doll factory and really one of the best scenes of the film.

With all the inertia of a 100-mile-an-hour car crash, the film shifts to 2014 Los Angeles. Borrowing heavily from Mulholland Drive, Seydoux becomes a stand-in for Lynch’s Naomi Watts. Here, Gabrielle is housesitting while attempting to find work as a struggling model and actress. Conversely, Louis becomes an Elliot Rodger-inspired misogynistic incel that rants about women to his mobile phone. With the tension of a modern slasher, the ill-fated love story plays out once again in the strange sun-soaked vision of Los Angeles.

Returning to 2044, the ending of the film is a gut punch that sticks, thanks in large part to Seydoux’s wonderfully believable performance.

It is difficult to get too far outside of the plot without ruining the film. Although, due to the nature of The Beast, it is both easy and hard to spoil. The plot doesn’t define the film, while the subtext alone would make it feel run-of-the-mill when it isn’t. There is something more here that, to explain in written form, would arguably blunt the splendor to be found in this otherwise highly cerebral yet ultimately dour-tinged film.

To boil it down, the greatest things in life often follow great anxiety. There is a shared humanity inherent in the trepidation of love and connection, which by extension makes it special and unique. It is the depth to which these things cause us great fear that they are also able to provide ultimate satisfaction. Human emotion is impractical, fickle, and nonsensical. To love knowing that someday it will cause heartbreak through either estrangement or death is impractical. But a life lived in practicality at the sacrifice of vulnerability is not a life lived. It isn’t human. It isn’t us.

But still, this is not all The Beast has to say. Bonello also slips in the sci-fi cornerstone of economic necessity crushing the human spirit and soul across time. Through this system, we must give away something of ourselves in order to stay fed. What then is a life lived in service of purely existing if it’s a life lived without feeling? Blunting the senses to simply exist. Never truly satisfied.

Unfortunately, Bonello’s scope and ambition are also possibly the film’s biggest flaws. In attempting to reimagine the humanistic revelations of the human spirit and reveal the psychology of love, trauma, and anxiety, there can be a mixture of themes and subtext that obscure the overall message. Despite wonderful direction and an ability to wring performances out of each lead, there is a free-flowing movement to the film that refuses to elaborate, connecting its own dots but only vaguely.

Where subjectivity can often allow art to be enjoyed and interpreted in one’s own way, there can often be too many ideas here that they get lost amongst themselves. Dolls, pigeons, fortune tellers. There are recurring motifs that often cause more confusion in the laundry list of accompanying strangeness that serve to detract rather than add.

There is a suggestion here that this film would ultimately benefit from repeat watches, although the lengthy runtime also makes that something of a difficult prospect. For these reasons, the average movie-going public will probably find themselves ostracized by this one. For those that love to follow a loose thread and find something at the end, it provides the perfect puzzle for the attentive viewer.

Despite its runtime, the interactions between leads are often enough to carry the film. While there isn’t much in the way of explicit excitement, both actors are committed to nuanced and range-filled performances. Seydoux genuinely turns in a performance that is a marvel to observe. Her range of emotions contrasting through time periods is astounding. George MacKay also does well with the absolute 180-degree heel turn that comes at the midpoint of the movie. And credit to MacKay for learning French exclusively for the first part of the film.

For some, The Beast will feel like torture. A seemingly disconnected mix-and-match of genres and drawn-out nonsense. I know because that was the reaction of those watching the film with me. Mirroring the film’s themes, it is easy to see how and why many will feel disconnected and mentally wander off before meeting the gut punch of an ending.

However, for those that connect with Bertrand Bonello’s time-jumping, genre-hopping pick-and-mix, there is an endless bounty of sweet, sour, and bitter treats to be picked at on rewatches. And yet, despite the way it hurts to watch, it is sure to end over and over again with the same shot in the heart that came the first time around.

Funny that.

Fun Fact:

Director Bernard Bonello wanted a non-French actor to replace recently deceased Gaspard Ulliel, so that the actor would not suffer from the comparison with Ulliel. A British actor, George McKay, was hired, but he did not speak French at all, so he learned it just for the role, thus confirming in Bonello’s eyes the English actors’ reputation of being hard workers.

COMMENTS